Italy is once again in the spotlight. As its banking system undergoes a slow-motion implosion – the country’s banks are weighed down by €360 billion of bad loans, of which €200bn are deemed insolvent – all eyes are now on the Renzi government. How did we get to this point? Though there have been some attempts in recent years at reforming the banking system, and at addressing the banks’ heavy share of bad debt, the policy pattern has been more or less the following: whenever the market stress on individual banks (or a set of banks) reached critical levels, the government would roll out a last-minute quick fix that would temporarily appease market tensions but would do very little to address the underlying cause of the banking sector’s systemic stress: the unprecedented collapse that the Italian economy has suffered over the past 5-6 years.

We should be very clear about this. Much has been said in recent months about the mismanagement of Italian banks: the rampant corruption, fraud and abuse; the widespread practice of distributing loans to friends and family; the unsavoury ties to politics, etc. There is some truth to this. But it is notthe chief cause of the Italian banking crisis, as many commentators have asserted or implied. The crisis is ‘the consequence of the longest and deepest recession in Italy’s history’, as the governor of the Italian central bank, Ignazio Visco, recently stated. As financial journalist Matthew Lynn writes: ‘Italy doesn’t have a banking crisis; it has a euro crisis’.

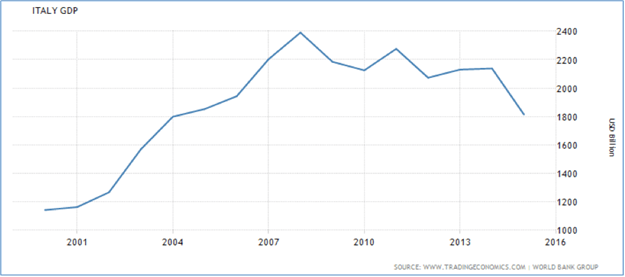

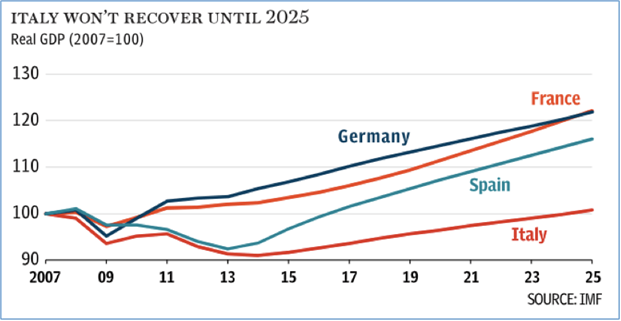

In macroeconomic terms, Italy has been the hardest hit country in the eurozone after Greece. Its GDP has shrunk by a massive 10 per cent since 2007, regressing to levels of over a decade ago. As a result, around 20 per cent of Italy’s industrial capacity has now been destroyed.

In terms of per capita GDP (PPP) the situation is even more shocking: according to this measure, Italy has regressed back to levels of 20 years ago.

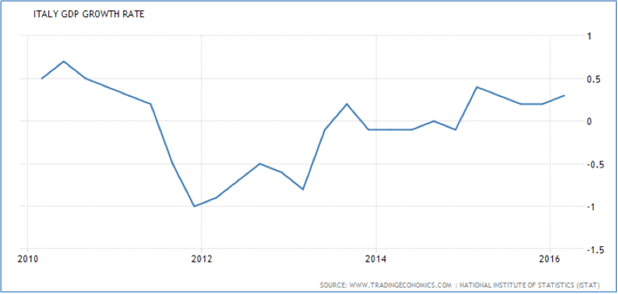

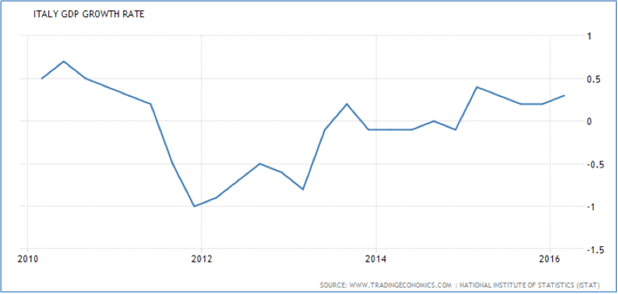

Of course, none of this is particularly surprising if we consider that Italy has essentially been in recession for the past six years.

Italy’s endemic structural problems – its supposedly hyper-rigid labour market, its bloated bureaucracy, its excessive tax rates, etc. – are notorious but it’s undeniable that the post-2011 economic collapse is a direct result of the austerity policies implemented by the Monti government in 2011-13 and since, including by the current Renzi government. After all, Monti himself admitted in an interview to CNN that his policies’ aim was ‘to destroy domestic demand through fiscal consolidation’, with the aim of rebalancing Italy’s current account deficit.

On its own terms, the policy worked: private consumption collapsed, imports fell and Italy’s current account deficit was turned into a minor surplus. But in an economy heavily dependent on domestic demand – Italy’s exports account for less than 30 per cent of total output – this was bound to take a very heavy toll. And it did. Just between 2009 and 2013, more than 1.7 million small and medium enterprises (SMEs) were forced to close. This, in turn, inevitably sent shockwaves throughout the banking system, which was and is heavily exposed to SMEs.

This is not just an Italian problem: the ECB’s recent stress tests have revealed that the banks with the largest capital shortfalls are all located in periphery countries. According to a recent study, for the EU as a whole, non-performing loans (NPLs) stood at over 9 per cent of GDP at the end of 2014 – equivalent to €1.2 trillion, more than double the level in 2009.

Now, after years of muddling through, the situation has finally exploded in the Italian government’s face. The proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back was the British referendum, which caused Italian bank stocks, which had been sliding for quite some time, to collapse to their lowest level in years.

It’s quite clear that a massive sell-off of Italian bank stock is underway, as testified by Italy’s TARGET2 levels, which have almost returned to 2012 peak-crisis levels.

It’s clear at this point that if radical measures are not taken to stabilise the banking system, there is a serious risk of systemic implosion. Another shock – political or financial – could easily trigger an all-out bank run in Italy. The cost of recapitalising the banks is typically estimated at around €40-45bn. The burning question is how the banks should be recapitalised. The EU’s banking union, which came into force in January 2016, prescribes that when a bank runs into trouble, existing stakeholders – namely, shareholders, junior creditors and, sometimes, even senior creditors and depositors with deposits in excess of the guaranteed amount of €100,000 – are required to take a loss before public funds can be used (either national funds or European Stability Mechanism (ESM) funds).

The European Commission and core countries – most notably Germany and the Netherlands – insist that Rome must stick by the rules and enforce a bail-in of junior creditors before resorting to a bailout. The government categorically refuses to do so and has insisted on being allowed to bail out the banks – a position backed by the ECB – while engaging in a wider battle against the current set-up of the banking union. Mr Visco, for example, has recently stated that that the current bail-in rules are exacerbating the Italian banking crisis rather than alleviating it.

Now, it would be easy to classify this as a classic example of Italian dodginess: complaining about rules that they were raving about until recently. And one would be justified for doing so. But this doesn’t change the fact that the bail-in rule is making things worse for the weaker banking sectors of the union – and for Italy’s banking sector in particular. And that is because enforcing the bail-in rule across the board, making it mandatory, as the banking union does – regardless of the nature of the banks’ problems, of the wider macroeconomic context of a country, etc. – clearly penalises the weaker capitals of the union (the ones located in the periphery) vis-à-vis the stronger ones (the ones located in the core countries), potentially leading to a foreign takeover of the former by the latter, thusexacerbating, rather than reducing, the core-periphery imbalances. Moreover, the rule clearly creates the conditions for self-fulfilling prophecies: if investors fear that a bank crisis is imminent, they will flee the country to avoid a bail-in, thus creating that very banking crisis that the banking union was supposed to avoid in the first place.

In economic terms, a bail-in of bondholders could easily end up freezing up the Italian domestic bond market, and could even trigger a bank run. Politically, it would be a disaster for the Italian government. And that is because the subordinated bonds that would take a hit are not simply owned by well-off families and other banks: as much as half of the €60 billion of subordinated bonds are estimated to be owned by around 600,000 small savers, who in many cases were fraudulently mis-sold these bonds by the banks as being risk-free (as good as deposits basically). It is not hard to see why forcing a loss on this category would be politically devastating for Renzi, who got a taste of the potential backlash in December, when the government forced losses onto the bondholders of four small banks. Some have argued that a bail-in could be made politically acceptable by bailing in junior debt holders today with the promise of reimbursing small savers that were victims of mis-selling later on. But a) this would not avoid the short-term political fallout; and b) there is no guarantee that the European Court of Justice (ECJ) would allow a reimbursement if there is a risk of this affecting financial stability.

An interesting new development is an ECJ ruling on the bail-in clause. Essentially, it confirmed the legality of the bail-in as a prerequisite for the authorisation of state aid, which would appear to weaken the Italian government’s negotiating position. At the same time, though, it also noted that the rules provide an exception if imposing a bail-in would endanger financial stability or lead to disproportionate results, which in turn may give Italy some leeway.

In the end, I think the Italian government and the European Commission will agree on a bailout. Ultimately, I don’t think the Commission wants to risk an immediate political crisis in Italy. Germany will end up softening its position, considering the problems that it is facing at home with Deutsche Bank, whose chief economist recently stated that European banks need a €150bn bailout.

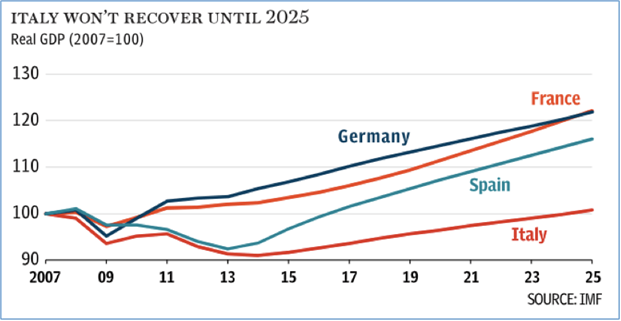

More worrying, though, is the fact that not even this will provide a long-term solution for Italy’s banks, or for the European banking system in general. The bottom line is that unless we see a sustained recovery in the real economy, these and other problems will just keep re-surfacing. Unfortunately, there is no prospect of recovery ahead. The IMF has recently estimated that Italy’s economy will not return to its pre-crisis size until 2025. That means that Italy faces not one, but two lost decades.

Clearly, this is not sustainable, neither economically nor politically. Ceteris paribus, I am willing to wager that the euro is unlikely to still be around in 2025.

About Thomas Fazi

Thomas Fazi is a writer, activist and award-winning filmmaker. He has also translated into Italian the works of authors such as Christopher Hitchens, George Soros and Robert Reich. His book, The Battle for Europe: How an Elite Hijacked a Continent - and How We Can Take It Back is published by Pluto Press. His website is www.battleforeurope.net

Get The Best Of Social Europe For